Building an 8 Node Raspberry Pi 4 Cluster (with Docker Swarm)

Most people visiting this blog have probably heard of the Raspberry Pi before. I’d wager that most people visiting this blog actually own at least one or more of the devices. I’ve actually lost count of how many I own at this point, and I just added 8 more to that number. They’re extremely useful and serve a wide variety of purposes.

For those that are somehow not in the know - a Raspberry Pi is a single board computer that’s roughly the dimensions of a credit card. Or like…a stack of 7 or 8 credit cards, with the IO ports. They’re remarkably capable devices, and the Raspberry Pi 4 is the most powerful device yet. They have 4 physical ARM cores on the device (with a base clock of 1.5GHz) and up to 8GB of LPDDR4-3200 SDRAM. They boot off of a micro SD card slotted into the device and can be powered over a 5V/3A DC connection through USB-C.

This is all to say that they’re small, they’re powerful, and they’re cheap. An absolutely maxed out Pi 4 costs a little under $100. For something that can single handedly fulfill almost all of your home server needs, that’s practically free - or at least a no-brainer investment to any sysadmin on a budget.

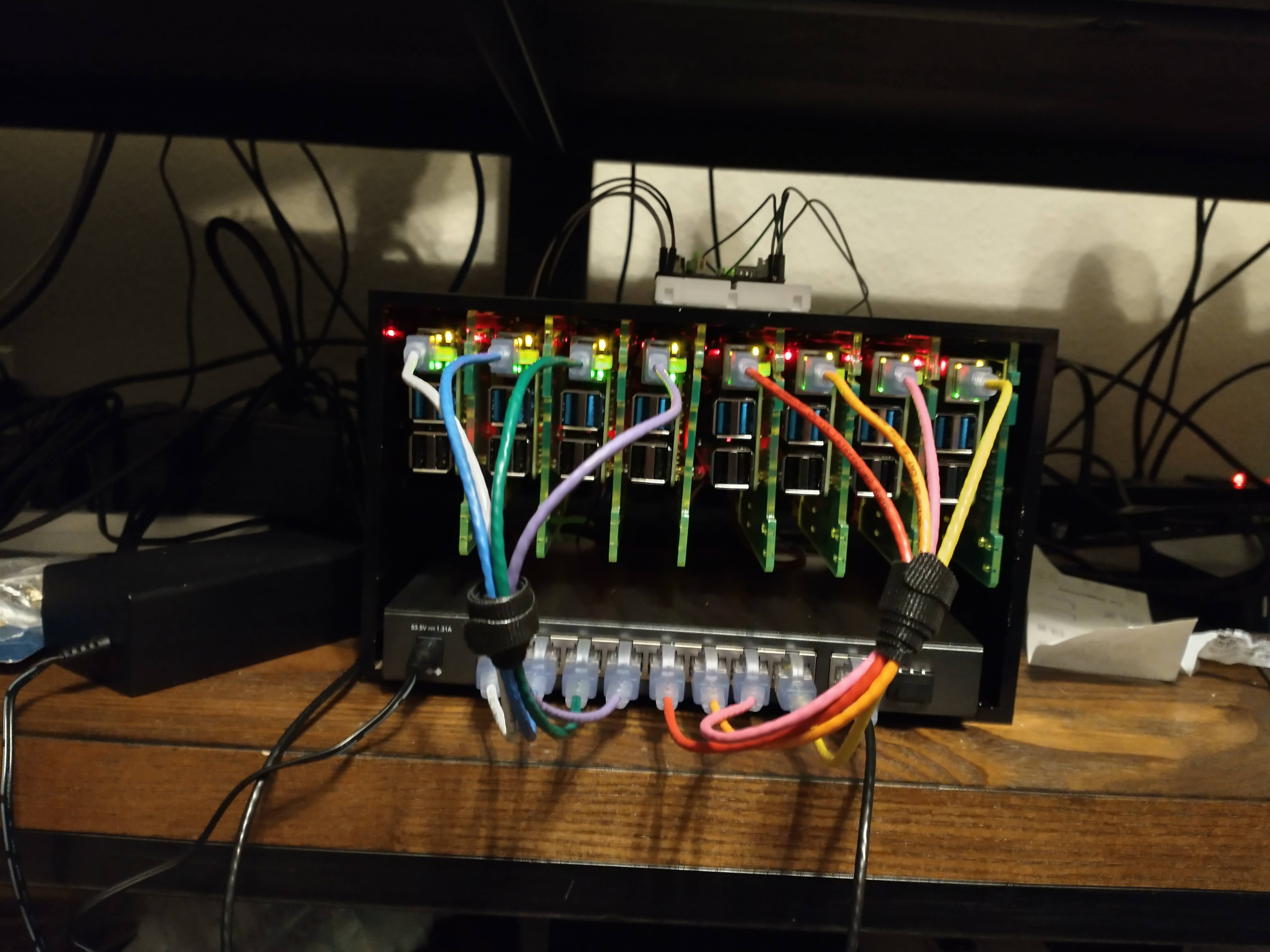

In lieu of a proper transition to the next section, here’s a picture of the cluster.

What are we going to do here?⌗

I wanna get you prepared to build your own Pi cluster, and learn from my mistakes. I’ll get you a list of materials, some setup instructions, and some rationalizations for my own choices.

Why did you build this?⌗

I’m so glad you asked. Unfortunately, that would be a rant worthy of its own post. Good news: I have made that post! For now though, let’s just carry on with the cluster itself.

Why not Kubernetes?⌗

I’m going to level with you, The Internet, I’m not a fan of Kubernetes. I’m not running a Google-scale operation out of my house. I’m really not a fan of YAML. I don’t need the complexity of Kubernetes, nor do I need the overhead associated with it. If I’m going to have to write YAML, it’s going to be YAML that I already now - like docker-compose specifications. That’s exactly what swarm mode runs off of.

TL;DR “swarm mode fits my needs and involves less configuration”

What you need⌗

As a forewarning, all of these links are Amazon Affiliate links.

- 8 Raspberry Pi 4B computers with 8GB of RAM

- 8 Raspberry Pi PoE+ Hats (specifically the PoE+ model to deliver up to 3A to each Pi - no link because I can’t find them anywhere)

- A C4Labs Cloudlet Cluster Case

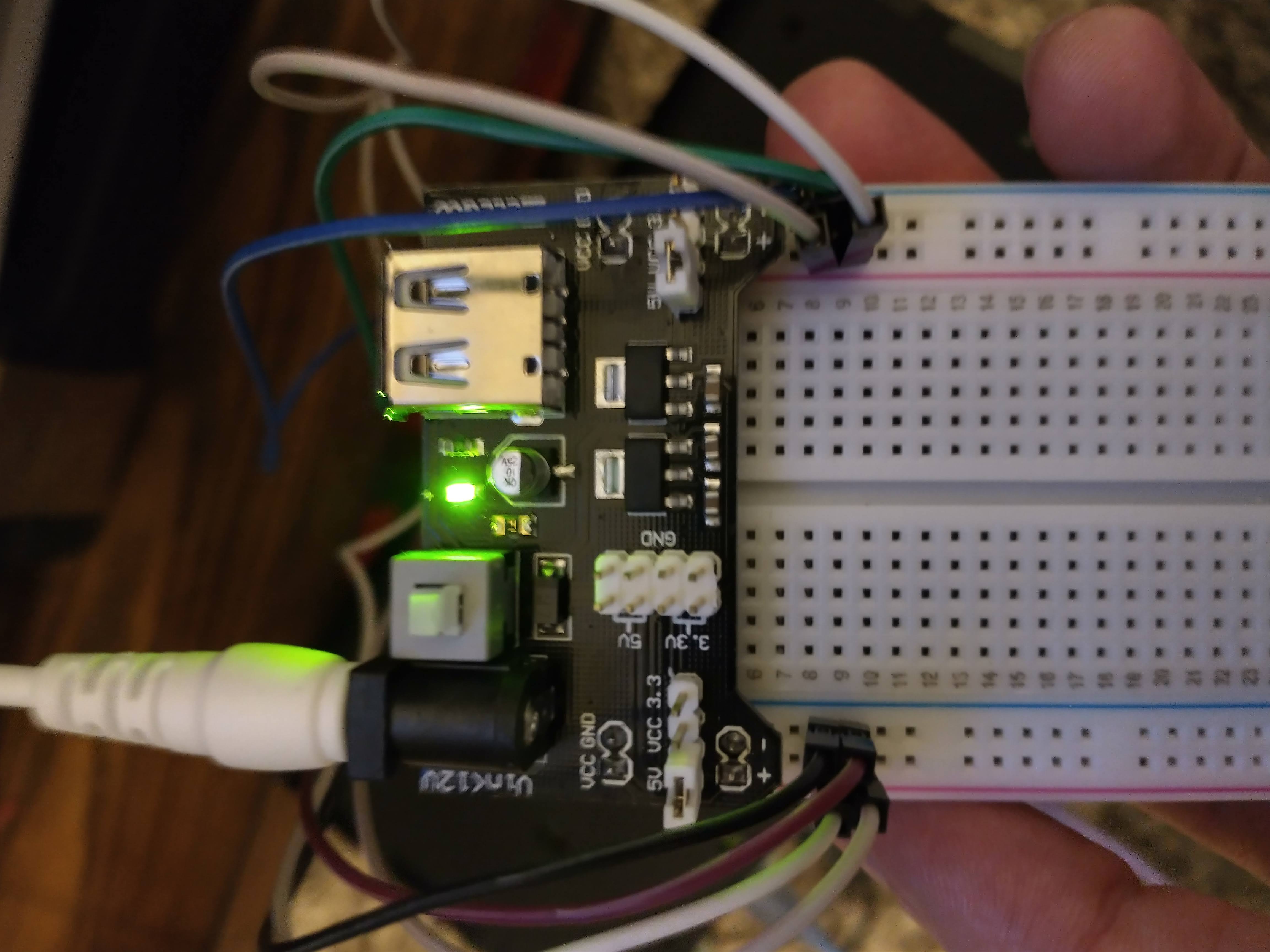

- A breadboard (or 4)

- Some jumper cables

- A breadboard power supply capable of delivering 5V

- A 9 port PoE ethernet switch

- Cat6A cables that support PoE and also look good

- 8x 128GB micro SD cards

- A really cool boss who buys you 5 of the 8 nodes for your birthday

- A nearly unlimited amount of patience

If that sounds like a lot of supplies or really expensive, that’s because it is! It’s stupidly expensive. It’s also stupidly overpowered, even for what I’m using it for. 5 of the nodes are dedicated to crunching and seeds, and 3 of the nodes have replaced every other server in my house. That’s a non-trivial amount of servers.

This is 32 physical cores at 1.5GHz (or a little more with a light overclock I have applied, but don’t do that) and 64GB of DDR4 RAM. This cluster collectively makes one ridiculous machine.

Corners you can cut⌗

You can build a cluster with a minimum of 2 nodes and it’s gonna work great.

You can build it without power over ethernet, which adds more cables but saves a ton of money.

You can use Raspberry Pis with less memory on them.

You can buy smaller micro SD cards for them (although I wouldn’t go below 64gb, and those are pretty cheap).

The cloudlet case is not strictly necessary. It cuts down on noise (enough that I would not run this cluster without it) and helps cooling performance, but eliminating that also gets rid of the breadboards + power supplies + jumper wires.

If you opt not to get the cloudlet case, I would recommend not getting the PoE hats. They generate an appreciable amount of heat and the fans they come equipped with are the most obnoxious thing I have ever heard. The cloudlet case has its own (much quieter) fans that are significantly more effective. We do leave the PoE hat fans still attached and functional, but we aim to keep the systems cool enough that they do not turn on.

Imaging!⌗

Raspberry Pis are ARM devices. What the Raspberry Pi company won’t tell you, however, is that they are 64-bit ARM devices. Raspbian ships as a 32-bit OS by default for legacy compatibility reasons, but we’re more interested in fully utilizing the hardware and not having to manually rebuild every Docker image we want to use. For some reason the 64 bit builds are hidden pretty well, but they’re available here. Download that image, flash it to all of your SD cards, and make sure you put an empty file named ssh into the boot partition of each SD card. This will enable the SSH daemon and allow you to connect to each of your Pis without needing to connect a keyboard and monitor.

Assembly!⌗

Screw the spacers onto your PoE hats, squish the hats onto the Pis, and attach the Pis to the cloudlet’s acrylic plates by screwing into the standoffs on the PoE hats. Before inserting the plates into the case, make sure to mount the 4 included fans onto the inside of the case. Run the jumper wires for them out of the case through the holes underneath them. Now you can insert the plates with Pis on them into the case. It’s a bit finnicky, but they click right in once you get them.

Now it’s time to set up cooling for our case before we turn it on. Take 8 male-to-male jumper wires and connect one end to the female jumper wires coming out from the fans. Remember which one goes to ground (the black wire) and which one goes to power (the red wire). Plug your breadboard power supply into the breadboard, and you’ll have 2 rails on either side that are now powered. Connect the red wires to one of the + rails and the black wires to the - rails.

These fans are designed to run at 5 volts, but will run with only 3.3v available if you need the cluster to run more quietly. I personally keep my cluster about 5 feet from my bed and find the quiet “whooshing” noise to be soothing white noise, unlike the whiny angry bee sounds of the PoE hats.

Make sure that this board is plugged in and the fans are on before you plug your Pis into your PoE switch. This will save your eardrums from so much pain.

Networking!⌗

This is where things get pretty specific to your setup. My router allows me to assign static local IPs to devices by mac address, so I did. I use 192.168.1.200-207 for mine. On first bootup I assigned them these addresses through my router and now they’re guaranteed to get those addresses every time they boot. This helps with cluster resiliency and addressing.

Provisioning!⌗

Boot up your Pis and let give them some time to resize their filesystem and come online. This can take a while, up to 5 or 10 minutes. Do not unplug them while this is happening. After that’s done, you can carry on to actually provisioning them.

Are you ready for the YAML part of the post? Because there’s no way to escape the YAML part. Everything is YAML nowadays.

Here’s the Ansible playbook I use to provision all of the Pis. It authorizes my public key for SSH access as well as their own, and gives them open access between each other.

Not pictured in this playbook is me changing all of their passwords away from the default and changing their hostnames to manager1 and worker1 through worker7. I also installed and configured tailscale on all of them so that I can use them for CPU offload from my main hobby server without having to forward ports on my router. This adds a small amount of latency (~15-20ms) but is incredibly worth it for the security benefits and ease of configuration in my opinion.

---

- hosts: all

become: yes

tasks:

- name: Authorize SSH keys

ansible.posix.authorized_key:

user: pi

state: present

key: '{{ item }}'

with_file:

- ./id_rsa.pub

- ./pi_rsa.pub

- name: Copy SSH private key

copy:

src: ./pi_rsa

dest: /home/pi/.ssh/id_rsa

mode: '0600'

- name: Copy SSH public key

copy:

src: ./pi_rsa.pub

dest: /home/pi/.ssh/id_rsa.pub

mode: '0644'

- name: Run updates

apt:

update_cache: true

upgrade: dist

- name: Install packages

apt:

update_cache: true

pkg:

- python3

- python3-pip

- vim

- gnupg2

- pass

- curl

- name: Download the docker install script

command: curl -fsSL https://get.docker.com -o get-docker.sh

- name: Run it

command: sudo sh get-docker.sh

- name: Enable the services

service:

name: '{{ item }}'

enabled: true

state: started

loop:

- docker

- containerd

- name: Add pi user to docker group

user:

name: pi

groups: docker

append: yes

- name: Create mount points

file:

path: '/mnt/nfs/{{ item }}'

state: directory

loop:

- pi-cluster

- plex

- transmission

- name: Add NFS mounts

lineinfile:

path: /etc/fstab

line: '192.168.1.2:/{{ item }} /mnt/nfs/{{ item }} nfs4 defaults,user,relatime,rw 0 0'

loop:

- pi-cluster

- plex

- transmission

- name: Add the /shared symlink

file:

src: /mnt/nfs/pi-cluster

dest: /shared

state: link

- name: Wait for network on boot

command: raspi-config nonint do_boot_wait 0

- name: Resolve cluster hostnames locally

lineinfile:

path: /etc/hosts

line: '{{ item }}'

loop: "{{ lookup('file', './hosts-list.txt').splitlines() }}"

- name: Reboot

reboot:

This also mounts my NAS as shared storage for them and ensures they mount those directories on boot by waiting for networking first.

Once this is done, it’s time to go in and connect all of the Pis via docker swarm. On your manager node, run docker swarm init. This will print out a command with a join token for your worker nodes - go run that on every one of your workers.

You now have a docker swarm cluster! By routing to the IP address of any of the nodes, you can access the overlay network and therefore any services you have running on it. Right now, you have nothing on there. Let’s make it a liiiiiittle bit more useful.

Adding visualization!⌗

Portainer is a popular visual cluster management tool that is web based. It also fortunately supports docker swarm right out of the box, and even has a preconfigured stack definition for you available here.

SSH into your manager node and follow their instructions for downloading and deploying the stack:

$ curl -L https://downloads.portainer.io/portainer-agent-stack.yml -o portainer-agent-stack.yml

$ docker stack deploy -c portainer-agent-stack.yml portainer

Go to one of your nodes (I have my manager node aliased as cluster.gov on my network) on port 9000 in your web browser to see the Portainer management UI. I primarily use this just to see which services are running where.

Adding a private registry!⌗

Sometimes you need custom built services designed specifically for your cluster. In my use case, this was a must have. Fortunately, deploying a private registry is as easy as creating the following service definition:

version: '3'

services:

registry:

image: registry:2

ports:

- 5000:5000

volumes:

- /shared/registry:/var/lib/registry

Aaaaaand configure the docker daemon on each host to allow insecure communications to that registry since it will be running solely on this cluster network:

{

"insecure-registries": ["localhost", "cluster.gov:5000", "localhost:5000", "192.168.1.200:5000"]

}

The hostnames and IP addresses will vary based on your network setup, so make sure you adjust those as needed. After that’s set up, give every node one last reboot and you’ll be good to go! Your nodes will now communicate amongst themselves and schedule tasks based on the available resources on each node.

What now?⌗

Now is up to your imagination. You can use this cluster for pretty much anything you would use any other system with Docker installed on it for. I’ve personally got mine running Plex media server, the AV seed ingest project, my dynamic DNS agent, and a couple of Twitch/Discord bots.

I highly recommend reading the companion post to this one, describing the insane brute-force search I built this for.